前期出版

前期出版

頁數:1﹣71

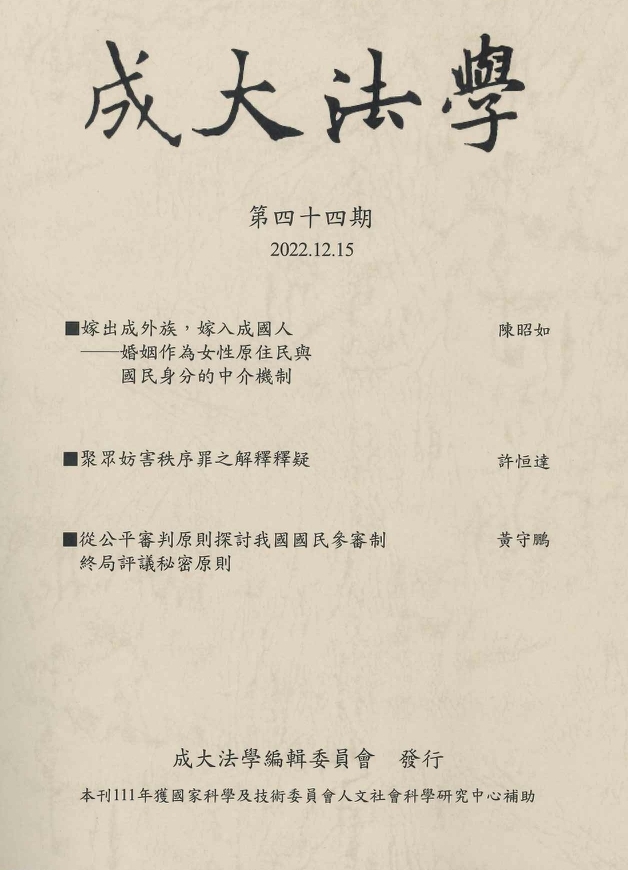

嫁出成外族,嫁入成國人──婚姻作為女性原住民與國民身分的中介機制

Marry out and Become an Outsider, Marry in and Become a Citizen: Marriage as a Mediating Mechanism of Women’s Indigenous Status and Nationality

研究論文

作者(中)

陳昭如

作者(英)

Chao-Ju Chen

關鍵詞(中)

國籍、原住民身分、婚姻、女性主義、批判種族理論、交織性

關鍵詞(英)

Nationality, Indigenous Status, Marriage, Feminism, Critical Race Theory, Intersectionality

中文摘要

婚姻制度製造性別不平等的方式之一是要求妻子的身分從屬於丈夫。戰後臺灣歷史上曾有兩類女性身分從夫的法律規範,一是「嫁出條款」,這主要存在於原住民身分相關法律規定,使原民女性因與非原民結婚而失去原民身分;二是「嫁入條款」,這主要存在於國籍法規定,讓外國女性因與本國男性結婚而當然取得我國國籍。本文以女性主義法學理論與批判種族理論探討嫁出與嫁入條款的女性主義法律史(1945年至2001年),檢視政府如何透過法律與政策以強制和自願並行的方式將婚姻作為中介女性的國民與原住民身分的機制,此機制如何經歷了「中性化」與「自願化」的改革,並指出在廢除嫁出與嫁入條款,且立法明訂通婚原住民的身分回復權之後,性別與種族交織的歧視仍繼續存在。

本文的研究發現,嫁出與嫁入條款共同作為製造女性從屬性的機制,讓女性因「嫁出」成外族、因「嫁入」成國人。原民與移民女性在國籍法與原住民身分法改革中皆被雙重邊緣化,但二者的發展有別:原民的嫁入條款之廢除與身分回復主要是因為原民運動對抗種族滅亡的主張;國籍法上嫁入條款的廢除則與臺灣社會的假結婚焦慮、性平運動和洋女婿爭權運動有關。本文最後主張,處理性別與種族交織歧視的關鍵是自治與自願的難題。

本文的研究發現,嫁出與嫁入條款共同作為製造女性從屬性的機制,讓女性因「嫁出」成外族、因「嫁入」成國人。原民與移民女性在國籍法與原住民身分法改革中皆被雙重邊緣化,但二者的發展有別:原民的嫁入條款之廢除與身分回復主要是因為原民運動對抗種族滅亡的主張;國籍法上嫁入條款的廢除則與臺灣社會的假結婚焦慮、性平運動和洋女婿爭權運動有關。本文最後主張,處理性別與種族交織歧視的關鍵是自治與自願的難題。

英文摘要

One of the ways that the institution of marriage generates gender inequality is to subordinate the group status of the wife to her husband’s. In postwar Taiwan, there were two kinds of laws that mediated women’s group statuses through marriage and rendered a wife her husband’s subordinate: the marry-out rule or marital expatriation, which deprived a woman of her membership due to her marriage with an outsider, mainly in the case of an indigenous woman marrying a non-indigenous man; and marital naturalization, which mandated that a woman became the member of her husband’s community, primarily in the case of a foreign woman marrying a male citizen. Through the lens of feminist legal theory and critical race theory, this study investigates the feminist legal history of marital expatriation and marital naturalization from 1945 to 2001, reviewing how the government had made the institution of marriage a medium of women’s citizen and Indigenous status through legal and administrative means in mandatory and voluntary ways, and reveals how laws and policies enforcing the subordination of a wife to her husband underwent a choice-oriented reform toward gender-neutralization. It also demonstrates and explains the remaining intersection of race and gender discrimination after the abolishment of the marry-out rule of Indigenous status law in 1991, the marital naturalization clause in the Nationality Act in 2000, and the legislation of the right to restore one’s Indigenous status in 2001. This study finds that laws of marital expatriation and marital naturalization had functioned to faciliate women’s subordination by making an out-marrying Indigenous woman a non-member of her racial group and a foreign woman a citizen of her husband’s country. Indigenous and migrant women were marginalized in the legal reform process. It also finds significant differences between the legal reform of nationality and Indigenous status. The formation of the marry-out rule for Indigenous peoples concerned the controversy over women’s political participation, the anxiety over Indigenous men’s lack of marriage opportunities, and the material distribution of lands and resources. The Indigenous movement’s advocacy for group survival has led to the abolishment of the marry-out rule. In contrast, the abolishment of marital naturalization was associated with the collective anxiety over sham marriages, the gender equality movement, and the foreign son-in-law’s rights movement. As a final thought, this study suggests that resolving the dilemma of self-determination and consent is the key to combating the intersectional discrimination of race and gender.

線上閱覽

全文下載get_app

1.全文公開下載